Últimos assuntos

Tópicos mais visitados

Tópicos mais ativos

Darwin também errou sobre a seleção natural

Página 1 de 1

04022010

Darwin também errou sobre a seleção natural

Darwin também errou sobre a seleção natural

Marcelo Gleiser e o erro de Darwin

JC e-mail 4065, de 02 de agosto de 2010.

27. O erro de Darwin, artigo de Marcelo Gleiser

"Devemos julgar afirmações sobre 'teorias de tudo' com enorme ceticismo; nosso conhecimento é limitado"

Marcelo Gleiser é professor de física teórica no Dartmouth College, em Hanover (EUA). Artigo publicado na "Folha de SP":

Em 1859, com o furor de uma mente devota, o já não tão jovem Charles Robert Darwin, com 50 anos, publica seu segundo livro, " On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favored Races in the Struggle for Life" [A origem das espécies através da seleção natural ou a preservação das raças favorecidas na luta pela vida].

Nele, o então cientista principiante propõe nada menos do que a solução final para a origem das espécies: o plano totalmente natural e mecanicista através da seleção natural.

Segundo Darwin, tudo se deu durante uma leitura desinteressada que fez da Malthus em 1837. Segundo sua autobiografia publicada em 1876, quando lia o princípio malthusiano sobre o crescimento geométrico dos alimentos e o crescimento aritmético das populações, Darwin teve um estalo epistêmico a la Arquimedes:

Se a produção de mais descendentes que podem sobreviver estabelece um ambiente competitivo entre os aparentados, e a variação entre eles produziria alguns indivíduos com maiores chances de sobrevivência, se este princípio malthusiano estivesse correto, isso era sintoma de sua aplicabilidade em uma ordem muito mais profunda.

Eureka! Voilá! Talvez a estrutura biológica seguisse as regras da economia. Fosse esse o caso, a mente humana teria acesso direto aos segredos mais profundos da natureza sem precisar de nenhuma ajuda externa. E a língua em comum entre o homem e a origem das espécies somente seria melhor explicada através da seleção natural ao longo de longas eras.

Após várias tentativas teóricas frustradas, Darwin somente obteve a solução epistêmica que tanto almejava após receber em 1858 o ensaio teórico de Alfred Rusell Wallace muito superior às suas ideias. Na época, alguns naturalistas já falavam em seleção natural e outros mecanismos evolucionistas. Mas a seleção natural era invisível aos olhos europeus vitorianos.

Todavia, Darwin, numa sacada genial, pediu permissão aos leitores para “apresentar um ou dois exemplos imaginários [da ação da seleção natural]”: o lobo e a captura de suas presas [pela astúcia, força e agilidade] e o entrecruzamento de duas flores de plantas distintas através de um líquido/néctar também imaginário, que transmitiriam essas características aos seus descendentes, e assim os mais aptos sobreviveriam devido ao processo de preservação contínua. Portanto, a origem das espécies seria, principalmente, segundo Darwin, decorrente da seleção natural entre outros mecanismos evolutivos!

Darwin foi além, mas precavido. Ele tinha plena consciência de que a sua (e de Alfred Rusell Wallace também) teoria da seleção natural, ilustrada com dois exemplos imaginários, sofreria objeções científicas. Mesmo tendo apenas dois exemplos imaginários, Darwin afirmou que “a seleção natural só pode agir através da preservação e acumulação de modificações hereditárias infinitesimalmente pequenas, desde que úteis ao ser modificado”.

Para um homem que acreditava profundamente na natureza, nada mais natural do que uma solução natural. Darwin via seu arranjo como a expressão do sonho dos filósofos gregos antigos de obter uma explicação estritamente naturalista para os mistérios do mundo. Para ele, a teoria da seleção natural [o mais importante entre outros mecanismos evolutivos] era a teoria biológica final para explicar a origem das espécies.

Podemos aprender algo com Darwin. Soubesse ele da existência da complexidade irredutível dos sistemas biológicos, e da informação complexa especificada, como teria reagido? Certamente, seu sonho de uma ordem natural para as coisas vivas dependia do que se sabia na época. Seu erro foi ter dado ao estado do conhecimento empírico do mundo o valor epistêmico para o mero acaso, a fortuita necessidade, e a ação cega da seleção através de longas eras, numa teoria de longo alcance histórico de difícil corroboração no contexto de justificação teórica. Uma Theoria perennis. Uma teoria final.

Para Charles Robert Darwin, era inimaginável que a origem das espécies pudesse se desviar desta estrutura de mero acaso, fortuita necessidade, através da seleção natural. No entanto, sabemos que nosso conhecimento do mundo é limitado, e será sempre.

Por isso, devemos julgar declarações sobre teorias de tudo ou teorias finais com enorme ceticismo, inclusive a teoria da evolução através da seleção de Darwin. Afinal de contas, a história da ciência nos ensina que o progresso científico caminha de mãos dadas com nossa habilidade de medir a natureza. Achar que a mente humana pode imaginar a origem das espécies antes de verificá-la empiricamente pode, ocasionalmente, dar certo. Mas, em geral, leva a teorias que existem apenas na imaginação. Como os exemplos de ação da teoria da seleção natural de Darwin, uma teoria nos seus estertores epistêmicos demandando uma revisão nos seus fundamentos, ou siplesmente descarte, e que outra teoria tome seu lugar: a Síntese Evolutiva Ampliada, que, pelas montanhas de evidências contrárias, não pode mais ser selecionista a la Darwin.

+++++

Baseado em texto publicado na Folha de SP, 1/8/2010, e republicado no JC e-mail 4065, de 02 de agosto de 2010, "O erro de Kepler".

+++++

Vote neste blog para o prêmio TOPBLOG.

Darwin também errou sobre a seleção natural

Survival of the fittest theory: Darwinism's limits

03 February 2010 by Jerry Fodor and Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini

Magazine issue 2746

READERS in search of literature about Darwin or Darwinism will have no trouble finding it. Recent milestone anniversaries of Darwin's birth and of the publication of On the Origin of Species have prompted a plethora of material, so authors thinking of adding another volume had better have a good excuse for it. We have written another book about Darwinism, and we urge you to take it to heart. Our excuse is in the title: What Darwin Got Wrong.

Much of the vast neo-Darwinian literature is distressingly uncritical. The possibility that anything is seriously amiss with Darwin's account of evolution is hardly considered. Such dissent as there is often relies on theistic premises which Darwinists rightly say have no place in the evaluation of scientific theories. So onlookers are left with the impression that there is little or nothing about Darwin's theory to which a scientific naturalist could reasonably object. The methodological scepticism that characterises most areas of scientific discourse seems strikingly absent when Darwinism is the topic.

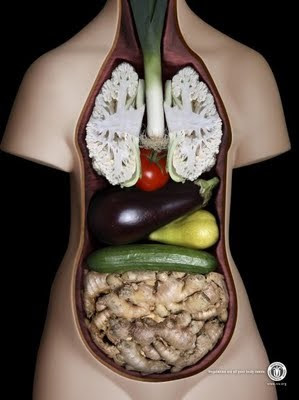

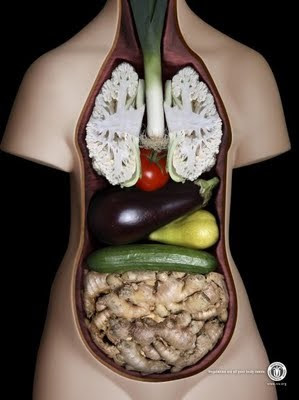

If Darwin had known what we know now, he might have come to different conclusions (Image: Anna Gowthrope/PA Wire/AP)

Try these descriptions of natural selection, typical of the laudatory epithets which abound in the literature: "The universal acid" (philosopher Daniel Dennett in Darwin's Dangerous Idea, 1995); "a mechanism of staggering simplicity and beauty... [it] has been called the greatest idea that anyone ever had... it also happens to be true" (biologist Jerry Coyne in Why Evolution is True, 2009); "the only workable theory ever proposed that is capable of explaining life we have" (biologist and ethologist Richard Dawkins, variously). And as Dennett continues in Darwin's Dangerous Idea: "In a single stroke, the idea of evolution by natural selection unifies the realm of life, meaning, and purpose with the realm of space and time, cause and effect, mechanism and physical law."

Golly! Could Darwinism really be that good?

Darwin's theory of evolution has two connected parts: connected, but not inseparable. First, there is an explanation of the taxonomy of species. It is an ancient observation that if you sort species by similarities among their phenotypes (a phenotype being a particular creature's collection of overt, heritable biological properties) they form the hierarchy known as a "taxonomic tree".

This is why most vertebrate species are more similar to one another than they are to any invertebrate species, most species of mammals are more similar to one another than they are to any species of reptiles, and so forth. Why is this? It is quite conceivable that every species might be equally different from every other. What explains why they aren't?

Darwin suggested a genealogical hypothesis: when species are relatively similar, it's because they are descended from a relatively recent common ancestor. In some ways, chimps seem a lot like people. This is not because God created them to poke fun at us, or vice versa; it is because humans and chimps are descended from the same relatively recent primitive ape.

The current consensus is that Darwin was almost certainly right about this. There are plausible exceptions, notably similarities that arise from evolutionary convergence, but evidence from a number of disciplines, including genetics, evolutionary developmental biology and palaeontology argues decisively for Darwin's historical account of the taxonomy of species. We agree that this really was as brilliant an idea as it is generally said to be.

But that cannot be the whole story, since it is not self-evident why species that have a recent common ancestor - as opposed, say, to species that share an ecology - are generally phenotypically similar. Darwin's theory of natural selection is intended to answer this question. Darwinists often say that natural selection provides the mechanism of evolution by offering an account of the transmission of phenotypic traits from generation to generation which, if correct, explains the connection between phenotypic similarity and common ancestry.

Moreover, it is perfectly general: it applies to any species, independent of what its phenotype may happen to be. And it is remarkably simple. In effect, the mechanism of trait transmission it postulates consists of a random generator of genotypic variants that produce the corresponding random phenotypic variations, and an environmental filter that selects among the latter according to their relative fitness. And that's all. Remarkable if true.

Compelling evidence

But we don't think it is true. A variety of different considerations suggesting that it is not are mounting up. We feel it is high time that Darwinists take this evidence seriously, or offer some reason why it should be discounted. Our book about what Darwin got wrong reviews in detail some of these objections to natural selection and the evidence for them; this article is a brief summary.

Here's how natural selection is supposed to work. Each generation contributes an imperfect copy of its genotype - and thereby of its phenotype - to its successor. Neo-Darwinism suggests that such imperfections arise primarily from mutations in the genomes of members of the species in question.

What matters is that the alterations of phenotypes that the mechanisms of trait transmission produce are random. Suppose, for example, that a characteristic coloration is part of the phenotype of a particular species, and that the modal members of the ith generation of that species are reddish brown. Suppose, also, that the mechanisms that copy phenotypes from each generation to the next are "imperfect" in the sense given above. Then, all else being equal, the coloration of the i + 1th generation will form a random distribution around the mean coloration of the parent generation: most of the offspring will match their parents more or less, but some will be more red than brown, and some will be more brown than red.

This assumption explains the random variation of phenotypic traits over time, but it doesn't explain why phenotypic traits evolve. So let's further assume that, in the environment that the species inhabits, the members with brownish coloration are more "fit" than the ones with reddish coloration, all else being equal. It doesn't much matter exactly how fitness is defined; for convenience, we'll follow the current consensus according to which an individual's relative fitness co-varies with the probability that it will contribute its phenotypic traits to its offspring.

Given a certain amount of conceptual and mathematical tinkering, it follows that, all else again being equal, the fitness of the species's phenotype will generally increase over time, and that the phenotypes of each generation will resemble the phenotype of its recent ancestors more than they resemble the phenotypes of its remote ancestors.

That, to a first approximation, is the neo-Darwinian account of how phenotypes evolve. To be sure, some caveats are required. For example, even orthodox Darwinists have always recognised that there are plenty of cases where fitness doesn't increase over time. So, for example, fitness may decrease when a population becomes unduly numerous (that's density-dependent selection at work), or when a species having once attained a "fitness plateau" then gets stuck there, or, of course, when the species becomes extinct.

Such cases do not show that neo-Darwinism is false; they only show that the "all else being equal" clauses must be taken seriously. Change the climate enough and the next generation of dinosaurs won't be more fit than its parents. Hit enough dinosaurs with meteors, and there won't be a next generation. But that does not argue against Darwinian selection, as this claims only to say what happens when the ecology doesn't change, or only changes very gradually, which manifestly does not apply in the case of the dinosaurs and the meteorite strikes.

So much for the theory, now for the objections. Natural selection is a radically environmentalist theory. There are, therefore, analogies between what Darwin said about the process of evolution of phenotypes and what the psychologist B. F. Skinner said about the learning of what he called "operant behaviour" - the whole network of events and factors involved in the behaviour of humans and non-human animals.

Driven from within

These analogies are telling. Skinner's theory, though once fashionable, is now widely agreed to be unsustainable, largely because Skinner very much overestimated the contribution that the structure of a creature's environment plays in determining what it learns, and correspondingly very much underestimated the contribution of the internal or "endogenous" variables - including, in particular, innate cognitive structure.

In our book, we argue in some detail that much the same is true of Darwin's treatment of evolution: it overestimates the contribution the environment makes in shaping the phenotype of a species and correspondingly underestimates the effects of endogenous variables. For Darwin, the only thing that organisms contribute to determining how next-generation phenotypes differ from parent-generation phenotypes is random variation. All the non-random variables come from the environment.

Suppose, however, that Darwin got this wrong and various internal factors account for the data. If that is so, there is inevitably less for environmental filtering to do.

The consensus view among neo-Darwinians continues to be that evolution is random variation plus structured environmental filtering, but it seems the consensus may be shifting. In our book we review a large and varied selection of non-environmental constraints on trait transmission. They include constraints imposed "from below" by physics and chemistry, that is, from molecular interactions upwards, through genes, chromosomes, cells, tissues and organisms. And constraints imposed "from above" by universal principles of phenotypic form and self-organisation - that is, through the minimum energy expenditure, shortest paths, optimal packing and so on, down to the morphology and structure of organisms.

Over the aeons of evolutionary time, the interaction of these multiple constraints has produced many viable phenotypes, all compatible with survival and reproduction. Crucially, however, the evolutionary process in such cases is not driven by a struggle for survival and/or for reproduction. Pigs don't have wings, but that's not because winged pigs once lost out to wingless ones. And it's not because the pigs that lacked wings were more fertile than the pigs that had them. There never were any winged pigs because there's no place on pigs for the wings to go. This isn't environmental filtering, it's just physiological and developmental mechanics.

So, how many constraints on the evolution of phenotypes are there other than those that environmental filtering imposes? Nobody knows, but the picture now emerging is of many, many of them operating in many, many different ways and at many, many different levels. That's what the evolutionary developmental school of biology and the theory that gene regulatory networks control our underlying development both suggest. And it strikes us as entirely plausible.

It seems to us to be no coincidence that neo-Darwinian rhetoric in the literature of experimental biology has cooled detectably in recent years. In its place, we find evolutionary biologist Leonid Kruglyak being quoted in Nature in November 2008 (vol 456, p 18) thus: "It's a possibility that there's something [about the contributions of genomic structure to the evolution of complex phenotypes] we just don't fundamentally understand... That it's so different from what we're thinking about that we're not thinking about it yet."

And then there is this in March 2009 from molecular biologist Eugene Koonin, writing in Nucleic Acids Research (vol 37, p 1011): "Evolutionary-genomic studies show that natural selection is only one of the forces that shape genome evolution and is not quantitatively dominant, whereas non-adaptive processes are much more prominent than previously suspected." There's quite a lot of this sort of thing around these days, and we confidently predict a lot more in the near future.

...

Read more here/Leia mais aqui: New Scientist

+++++

NOTA DESTE BLOGGER:

Desde 1998 este blogger deu adeus a Darwin no que diz respeito à explicação da origem e evolução das espécies. Gente, é desde 1859 que o homem que teve a maior ideia que toda a humanidade já teve não fecha as contas em um contexto de justificação teórica. E tome remendos teóricos: nos anos 1930s-1940s, a Síntese Evolutiva Moderna (ou neodarwinismo). Agora no século 21, a nova teoria geral da evolução - a SÍNTESE EVOLUTIVA AMPLIADA que, pelas razões apresentadas por Fodor e Piatelli-Palmarini e pelas evidências encontradas na natureza, não pode ser uma teoria evolucionária selecionista. Por quê? Porque até na seleção natural Darwin errou.

Fui, nem sei por que, pensando que mais uma vez evolucionistas de boa cepa como Fodor e Piatelli-Palmarini reinvindicam o que este blogger vem contestando há uma década.

Darwin? Ora, Darwin, morreu, gente! Viva Darwin, gente!

Por que a teoria da evolução através da seleção natural é pseudociência?

No livro Evolution From Space, Hoyle e Wickramasinghe apresentam sua objeção à teoria da evolução através da seleção natural (segundo alguns retóricos, a maior ideia que toda a humanidade já teve):

"A evolução darwiniana na sua maior parte é improvável de obter sequer corretamente um polipeptídeo, muito menos os milhares nos quais as células vivas dependem para sua sobrevivência. Esta situação é bem conhecida dos geneticistas, e ainda assim ninguém parece preparado para dar um apito na teoria."*

+++++

* "Darwinian evolution is most unlikely to get even one polypeptide right, let alone the thousands on which living cells depend for their survival. This situation is well known to geneticists and yet nobody seems prepared to blow the whistle on the theory." F. Hoyle & N. Wickrmasinghe, Evolution From Space (London: Dent, 1981), p. 148.

+++++

NOTA CAUSTICANTE DESTE BLOGGER:

A evolução através da seleção natural não tem a capacidade de criar [Argh, isso é como cometer um assassinato epistêmico] um simples polipeptídeo??? E eu pensei que era tão-somente incapaz de criar [Arg, agora eu cometi um holocausto epistêmico] um simples flagelo bacteriano! Eta mecanismo evolutivo incompetente e preguiçoso, sô!!!

Por que isso não aparece em nosso melhores autores de livros didáticos de Biologia do ensino médio aprovados pelo MEC/SEMTEC/PNLEM? Ué, o Prof. Dr. José Mariano Amabis não é geneticista? Por que não lida com esta dificuldade fundamental para o fato, Fato, FATO da evolução em seu livro junto com o Martho???

Em ciência a gente vive aprendendo cada uma...

Fui, nem sei por que, pensando que devo explorar mais o argumento destes dois astrofísicos ingleses que mandaram ver contra a Nomenklatura científica com suas inusitadas ideias científicas. Não atirem pedras neles não que o Francis Crick (do DNA) propôs uma ideia científica inusitada: a panspermia...

+++++

Vote neste blog para o prêmio TOPBLOG 2010.

Carlstadt- Administrador

- Mensagens : 1031

Idade : 48

Inscrição : 19/04/2008

Darwin também errou sobre a seleção natural :: Comentários

Ateu Critica Darwinistas Dogmáticos

O dogma tem que ser abandonado. Jerry Fodor, um filósofo na "Rutgers University", está perturbado com darwinistas dogmáticos que vêem a selecção natural como "pau para toda a obra" no que toca às mudanças evolutivas. Mas ele não é um criacionista: ele é um ateu convicto.

Ele debateu o seu livro What Darwin Got Wrong, co-escrito com Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini (professor ateu de Ciências Cognitivas na Universidade do Arizona) no site Salon.com. Thomas Rogers, que entrevistou Fodor, ficou surpreso com a existência de um ataque a Darwin que não partia da "Direita Religiosa".

Ele diz:

O problema de Fodor com a selecção natural é a sua propensão para contar histórias. Porque é que as pessoas possuem características como cabelo nas suas cabeças, e porque é que possuem cabelo escuro com olhos escuros?

Fodor afirma que não há forma de se saber quais eras as características que eram seleccionáveis por contribuírem para a aptidão, e quais as características que apareceram ao longo do caminho.

Agora imaginem o mesmo num ser vivo. Imaginem o que seria preciso levar em conta para transformar um dinossauro (um réptil) numa ave, ou transformar um animal 100% terrestre num animal 100% aquático. Pensem na forma de locomoção, comunicação, reprodução, visão, aleitamento, respiração e tudo o mais.

Estudarem-se características sem se levar em conta o todo é superficial e vazio. Os evolucionistas sabem disso, mas como não tem mais nada com que defender a sua fé, eles continua com a ilusão.

Conclusão:

Para quem segue com relativa atenção o que os órgãos de informação cristãos tem vindo a dizer, as palavras deste ateu não são novidade. A teoria da evolução é "uma actividade artificial", vazia, sem estrutura e sem valor científico algum. Inventar histórias sobre as "vantagens selectivas" duma características é tão válido (em termos científicos) como dizer que a fada madrinha gerou essa funcionalidade dum dia para o outro. Se é para ouvir histórias, talvez os evolucionistas devessem restringir as suas palestras aos jardins infantis, deixando os laboratórios de biologia para verdadeiros cientistas.

Adivinhação não é ciência, e a primeira permeia a teoria da evolução. Qualquer semelhança entre a evolução e a astrologia é pura coincidência.

O dogma tem que ser abandonado. Jerry Fodor, um filósofo na "Rutgers University", está perturbado com darwinistas dogmáticos que vêem a selecção natural como "pau para toda a obra" no que toca às mudanças evolutivas. Mas ele não é um criacionista: ele é um ateu convicto.

Ele debateu o seu livro What Darwin Got Wrong, co-escrito com Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini (professor ateu de Ciências Cognitivas na Universidade do Arizona) no site Salon.com. Thomas Rogers, que entrevistou Fodor, ficou surpreso com a existência de um ataque a Darwin que não partia da "Direita Religiosa".

Ele diz:

O livro de ambos mostra detalhadamente (em linguagem técnica) como as recentes descobertas na Genética questionam muitas das nossas "verdades" em torno da selecção natural, e como estas descobertas tem o potencial para fragilizar muito do que nós sabemos acerca da teoria da evolução e da Biologia.Por questionarem Darwin, Fodor e Piattelli-Palmarini receberam comentários obscenos nos blogs ateus e evolucionistas. Como é normal, os evolucionistas respondem a ataques à teoria da evolução com o seu tradicional fervor religioso fundamentalista.

O problema de Fodor com a selecção natural é a sua propensão para contar histórias. Porque é que as pessoas possuem características como cabelo nas suas cabeças, e porque é que possuem cabelo escuro com olhos escuros?

Tu podes inventar uma história para explicar como era bom ter essas propriedades no ambiente de selecção original. (...) Será que temos alguma razão para pensar que essa história corresponde a verdade? Não.Por outras palavras, a invocação à selecção natural permite aos evolucionistas inventarem qualquer tipo de histórias. Basta-lhes dizer que ter esta ou aquela característica era evolutivamente seleccionável, e pronto. Se é verdade ou não, isso é evolutivamente irrelevante. O que importa é que seja plausível.

Fodor afirma que não há forma de se saber quais eras as características que eram seleccionáveis por contribuírem para a aptidão, e quais as características que apareceram ao longo do caminho.

Dentro da visão darwinista não há nada que responda a questão:Fodor chega mesmo a afirmar que escolher uma característica pode ser irrelevante e sem sentido. A girafa tem um longo pescoço. Será que a natureza seleccionou característica, ou será que faz parte do "pacote de características" da girafa?

"Porque é que temos unhas nos pés?"

Será que há um propósito evolutivo? Como é que podemos saber? Até pode ser que no ambiente em que as unhas nos pés apareceram houvessem factores que favoreceram o seu aparecimento. Mas também pode ser que não.

(...)

Agora, a questão é: quanto da variação evolutiva é determinada por factores ambientais e quanta dessa mesma variação é controlada pela organização do organismo? A resposta é: ninguém sabe.

Os animais podem ter pescoços longos e unhas nos pés, mas se tu tentas particionar essa criatura em características, e dizes "Muito bem, O que é que seleccionou esta característica?", cometes um erro logo à partida. (...) A desintegração dum organismo em características é em si uma actividade artificial.Fodor acredita que a selecção trabalha no organismo como um todo, e isto não é difícil de se entender porquê. Imaginem o que é necessário para transformar um carro que anda sobre as estradas, num veículo de transporte 100% restrito a movimentar-se na água. De que é que me vale ir transformando o método de locomoção pouco a pouco, sem mudar, ao mesmo tempo, a forma de conter oxigénio dentro do carro, para quem estivesse lá dentro?

Agora imaginem o mesmo num ser vivo. Imaginem o que seria preciso levar em conta para transformar um dinossauro (um réptil) numa ave, ou transformar um animal 100% terrestre num animal 100% aquático. Pensem na forma de locomoção, comunicação, reprodução, visão, aleitamento, respiração e tudo o mais.

Estudarem-se características sem se levar em conta o todo é superficial e vazio. Os evolucionistas sabem disso, mas como não tem mais nada com que defender a sua fé, eles continua com a ilusão.

Conclusão:

Para quem segue com relativa atenção o que os órgãos de informação cristãos tem vindo a dizer, as palavras deste ateu não são novidade. A teoria da evolução é "uma actividade artificial", vazia, sem estrutura e sem valor científico algum. Inventar histórias sobre as "vantagens selectivas" duma características é tão válido (em termos científicos) como dizer que a fada madrinha gerou essa funcionalidade dum dia para o outro. Se é para ouvir histórias, talvez os evolucionistas devessem restringir as suas palestras aos jardins infantis, deixando os laboratórios de biologia para verdadeiros cientistas.

Adivinhação não é ciência, e a primeira permeia a teoria da evolução. Qualquer semelhança entre a evolução e a astrologia é pura coincidência.

Darwinism : The Refutation of a Myth (1987)

Introduction

It is doubtful if any single book, except the 'Principia', ever worked so great and so rapid a revolution in science, or made so deep an impression on the general mind [as On the Origin of Species]. 1

T.H. Huxley

… the name of Charles Darwin stands alongside of [that] of Isaac Newton … and, like [it], calls up the grand ideal of a searcher after truth and interpreter of Nature . . . [The present generation] thinkls] of him who bore it as a rare combination of genius, industry, and unswerving veracity, who earned his place among the most famous men of the age by sheer native power.!

T.H. Huxley

All educated persons are familiar with the notion that life on this planet has arisen through a process of evolution. Most people have been taught that the proper name of this theory is ‘Darwinism’, the reasons being that Charles Darwin was the first person to state the idea about organic evolution and furthermore originated the theory of natural selection, which unambiguously accounts for the mechanism through which the process of evolution is realised.

The concept of ‘evolution’ unites all branches of biology, and a person who accomplished these two feats would indeed be greatest among biologists, and might well deserve the epithet: ‘The Newton of Biology’. As appears from the above quotations, Huxley did not hesitate to bestow this honour upon his friend Charles Darwin.

In fact, this comparison was no invention of Huxley’s; ironically enough it appears that Alfred Wallace was the first to come upon this idea, for on 1 September 1860 he wrote to his friend George Silk: ‘Darwin’s “Origin of Species” … you may have heard of and perhaps read, but it is not one perusal which will enable any man

to appreciate it. I have read it through five or six times, each time with increasing admiration. It will live as long as the “Principia” of Newton. ,3

As might almost have been predicted, it was also heralded by Ernst Haeckel. Some few years after the publication of On the Origin of Species, quoting Immanuel Kant, he wrote:

‘ … it is absurd for man even to conceive such an idea, or to hope that a Newton may one day arise able to make the production of a blade of grass comprehensible, according to natural laws ordained by no intention; such an insight we must absolutely deny to man’. Now, however, this impossible Newton has really appeared seventy years later in Darwin, whose Theory of Selection has actually solved the problem, the solution of which Kant has considered absolutely inconceivable!”

Thus, Huxley was not the first, and still less the last one prepared to elevate Darwin to the pinnacles of glory in the history of biology; even today this opinion is shared almost unanimously by all who feel entitled to judge in these matters.

It is important to observe, however, that Huxley makes the comparison between Newton and Darwin with regard to two separate points: the impact of their work and their intellectual excellence.

Surely, no sensible person would contend Huxley’s first assertion; it is indeed true that no other book ever had the influence on the state of science commanded by On the Origin of Species. Is it a corollary that its author was a towering genius, foremost among biologists?

It may not be easy to give a direct answer to this question, and I shall therefore approach the problem by dealing with the two claims made above on behalf of Darwin. Thus (1) is Darwin the founder of the theory of evolution and (2) does his theory of natural selection give an acceptable explanation of the mechanism of evolution? If these two points are indeed borne out, then Darwin may well be the ‘Newton of Biology’ – otherwise not.

In this book I propose to show that in both instances the answer is ‘no’; and if I am right, we obviously end up in a rather awkward situation as far as present-day biology is concerned. But before we reach this point it would be well to outline the issue.

The main tenet of Darwin’s theory is that his natural selection accomplishes evolutionary changes through the accumulation of some of those very slight individual variations which occur in all populations of living beings. The selection of these variations, and hence the direction of evolution, is such that the organisms become

better adapted to the environment in which they happen to live.

Since the struggle for existence is bound to be toughest between adults, it follows that Darwin’s theory is a micromutation theory which accounts for evolutionary innovation primarily through the modification of adult organisms.

This theory was professed ex cathedra when I went to school, and for many years I accepted it without contemplation or dissent. Now and then I read literature dealing with evolution, but being an embryologist I did not think that evolution was of direct concern to me. I do not know when I first began to suspect that there is something questionable in the state of current evolutionary thought, but I know who aroused my suspicions – Karl Ernst von Baer’ and Richard B. Goldschmidt,” and it is because I am an embryologist that their teachings had this effect. These two zoologists quite clearly demonstrated that the origin of the major animal taxa must be sought in modifications of the epigenetic, and notably the morphogenetic processes through which the fertilised egg is transformed, first into an embryo or a larva, and subsequently to a slightly deformed miniature of the adult organism. (This last statement is not valid for animals that undergo extensive metamorphosis.) And the main inference from this insight is that many of the mutations which have been really important from an evolutionary point of view must have been one-stroke changes of features distinguishing disparate major taxa. In other words, the views of von Baer and Goldschmidt imply that macromutations have been of great significance in organic evolution.

I did not examine the consequences of this insight until I was engaged in writing Epigenetics – A Treatise on Theoretical Biology.’ This work aimed at elucidating some of the epigenetic mechanisms responsible for animal ontogenesis. Only at that time did I see that phylogenesis, i.e. evolution, is of primary concern for

epigenetics because phylogenetic innovations imply ontogenetic innovations. Hence I realised that my book would not be complete without a discussion of evolution, particularly a discussion of the consequences of the macromutation theory for our conception of the course and mechanism of evolution.

I therefore undertook a study of the literature on evolution, and made several discoveries which strengthened my conviction that the micromutation theory does not stand up to critical testing. Above all, I discovered that the so-called ‘Neo-Darwinism’ is fundamentally different from Darwin’s theory.

Since that time I have written several publications on evolution, adding steadily to the evidence falsifying the micromutation theory.

However, the most interesting discoveries were made when I began to delve into the history of evolutionary thought. First, I came to see what I should have realised at the outset, namely, that it is Lamarck, and not Darwin, who is the founder of the theory of evolution.

Second, I found that the macromutation theory is older than Darwinism, if not than the micromutation theory, and that it has had supporters, in varying numbers, for about one-and-a-half centuries.

Third, I came to understand that in the last century, hardly anybody, not even Darwin himself, believed that natural selection can accomplish all the events necessary for the occurrence of organic

‘evolution.

Fourth, I discovered that the history of evolutionary thought, as it is told today, contains a large number of mistakes and misrepresentations – to express it fairly mildly – all of them aimed at adulating Darwin and debunking his opponents.

Today it is still commonly claimed that Darwin’s natural selection is the evolutionary mechanism par excellence. However, this assertion is not based on any factual evidence, for nobody has ever demonstrated that natural selection can bring about anything but events that are trivial from an evolutionary perspective. And this brings me to the fifth point. Since the publication of On the Origin of Species, and particularly since the Second World War, a lot of empirical observations have been made which may be used to test the evolutionary theories. And the remarkable result is that, just as Darwin found one hundred years ago, the facts obstinately corroborate the macromutation theory and falsify the micromutation theory.

These are the main discoveries I have made in the course of my studies, and I propose to present them in detail on the following pages.

The championship of a heretical point of view is a delicate matter which requires better corroboration than might otherwise be called for. For this reason I have decided to let the dramatis personae speak their own cases as far as possible, and therefore a large part of the following text consists of quotations. This fact does not, of course, guarantee impartiality; against accusations of inequity I can only say that I have done my best. One circumstance which may serve to support this claim is that some persons, above all the principal actor,

Charles Darwin, are quoted to present divergent, even contradictory views.

Before we deal with Darwin’s contribution, we shall first discuss a set of four theories, which in my view are required to account for organic evolution, and some aspects of the history of evolutionary’ thought before Darwin. Subsequently we shall deal with Darwin’s theory, its reception and its fate during the following century. After that follows the presentation of an alternative theory of evolution, which stands up to the problems which have remained unsolved by Darwinism. At this stage, when, in my opinion, the Darwinian myth has been refuted, it may be appropriate to scrutinize it and try to understand why it arose in the first place.

+++++

HT/TC: Darwiniana

Introduction

It is doubtful if any single book, except the 'Principia', ever worked so great and so rapid a revolution in science, or made so deep an impression on the general mind [as On the Origin of Species]. 1

T.H. Huxley

… the name of Charles Darwin stands alongside of [that] of Isaac Newton … and, like [it], calls up the grand ideal of a searcher after truth and interpreter of Nature . . . [The present generation] thinkls] of him who bore it as a rare combination of genius, industry, and unswerving veracity, who earned his place among the most famous men of the age by sheer native power.!

T.H. Huxley

All educated persons are familiar with the notion that life on this planet has arisen through a process of evolution. Most people have been taught that the proper name of this theory is ‘Darwinism’, the reasons being that Charles Darwin was the first person to state the idea about organic evolution and furthermore originated the theory of natural selection, which unambiguously accounts for the mechanism through which the process of evolution is realised.

The concept of ‘evolution’ unites all branches of biology, and a person who accomplished these two feats would indeed be greatest among biologists, and might well deserve the epithet: ‘The Newton of Biology’. As appears from the above quotations, Huxley did not hesitate to bestow this honour upon his friend Charles Darwin.

In fact, this comparison was no invention of Huxley’s; ironically enough it appears that Alfred Wallace was the first to come upon this idea, for on 1 September 1860 he wrote to his friend George Silk: ‘Darwin’s “Origin of Species” … you may have heard of and perhaps read, but it is not one perusal which will enable any man

to appreciate it. I have read it through five or six times, each time with increasing admiration. It will live as long as the “Principia” of Newton. ,3

As might almost have been predicted, it was also heralded by Ernst Haeckel. Some few years after the publication of On the Origin of Species, quoting Immanuel Kant, he wrote:

‘ … it is absurd for man even to conceive such an idea, or to hope that a Newton may one day arise able to make the production of a blade of grass comprehensible, according to natural laws ordained by no intention; such an insight we must absolutely deny to man’. Now, however, this impossible Newton has really appeared seventy years later in Darwin, whose Theory of Selection has actually solved the problem, the solution of which Kant has considered absolutely inconceivable!”

Thus, Huxley was not the first, and still less the last one prepared to elevate Darwin to the pinnacles of glory in the history of biology; even today this opinion is shared almost unanimously by all who feel entitled to judge in these matters.

It is important to observe, however, that Huxley makes the comparison between Newton and Darwin with regard to two separate points: the impact of their work and their intellectual excellence.

Surely, no sensible person would contend Huxley’s first assertion; it is indeed true that no other book ever had the influence on the state of science commanded by On the Origin of Species. Is it a corollary that its author was a towering genius, foremost among biologists?

It may not be easy to give a direct answer to this question, and I shall therefore approach the problem by dealing with the two claims made above on behalf of Darwin. Thus (1) is Darwin the founder of the theory of evolution and (2) does his theory of natural selection give an acceptable explanation of the mechanism of evolution? If these two points are indeed borne out, then Darwin may well be the ‘Newton of Biology’ – otherwise not.

In this book I propose to show that in both instances the answer is ‘no’; and if I am right, we obviously end up in a rather awkward situation as far as present-day biology is concerned. But before we reach this point it would be well to outline the issue.

The main tenet of Darwin’s theory is that his natural selection accomplishes evolutionary changes through the accumulation of some of those very slight individual variations which occur in all populations of living beings. The selection of these variations, and hence the direction of evolution, is such that the organisms become

better adapted to the environment in which they happen to live.

Since the struggle for existence is bound to be toughest between adults, it follows that Darwin’s theory is a micromutation theory which accounts for evolutionary innovation primarily through the modification of adult organisms.

This theory was professed ex cathedra when I went to school, and for many years I accepted it without contemplation or dissent. Now and then I read literature dealing with evolution, but being an embryologist I did not think that evolution was of direct concern to me. I do not know when I first began to suspect that there is something questionable in the state of current evolutionary thought, but I know who aroused my suspicions – Karl Ernst von Baer’ and Richard B. Goldschmidt,” and it is because I am an embryologist that their teachings had this effect. These two zoologists quite clearly demonstrated that the origin of the major animal taxa must be sought in modifications of the epigenetic, and notably the morphogenetic processes through which the fertilised egg is transformed, first into an embryo or a larva, and subsequently to a slightly deformed miniature of the adult organism. (This last statement is not valid for animals that undergo extensive metamorphosis.) And the main inference from this insight is that many of the mutations which have been really important from an evolutionary point of view must have been one-stroke changes of features distinguishing disparate major taxa. In other words, the views of von Baer and Goldschmidt imply that macromutations have been of great significance in organic evolution.

I did not examine the consequences of this insight until I was engaged in writing Epigenetics – A Treatise on Theoretical Biology.’ This work aimed at elucidating some of the epigenetic mechanisms responsible for animal ontogenesis. Only at that time did I see that phylogenesis, i.e. evolution, is of primary concern for

epigenetics because phylogenetic innovations imply ontogenetic innovations. Hence I realised that my book would not be complete without a discussion of evolution, particularly a discussion of the consequences of the macromutation theory for our conception of the course and mechanism of evolution.

I therefore undertook a study of the literature on evolution, and made several discoveries which strengthened my conviction that the micromutation theory does not stand up to critical testing. Above all, I discovered that the so-called ‘Neo-Darwinism’ is fundamentally different from Darwin’s theory.

Since that time I have written several publications on evolution, adding steadily to the evidence falsifying the micromutation theory.

However, the most interesting discoveries were made when I began to delve into the history of evolutionary thought. First, I came to see what I should have realised at the outset, namely, that it is Lamarck, and not Darwin, who is the founder of the theory of evolution.

Second, I found that the macromutation theory is older than Darwinism, if not than the micromutation theory, and that it has had supporters, in varying numbers, for about one-and-a-half centuries.

Third, I came to understand that in the last century, hardly anybody, not even Darwin himself, believed that natural selection can accomplish all the events necessary for the occurrence of organic

‘evolution.

Fourth, I discovered that the history of evolutionary thought, as it is told today, contains a large number of mistakes and misrepresentations – to express it fairly mildly – all of them aimed at adulating Darwin and debunking his opponents.

Today it is still commonly claimed that Darwin’s natural selection is the evolutionary mechanism par excellence. However, this assertion is not based on any factual evidence, for nobody has ever demonstrated that natural selection can bring about anything but events that are trivial from an evolutionary perspective. And this brings me to the fifth point. Since the publication of On the Origin of Species, and particularly since the Second World War, a lot of empirical observations have been made which may be used to test the evolutionary theories. And the remarkable result is that, just as Darwin found one hundred years ago, the facts obstinately corroborate the macromutation theory and falsify the micromutation theory.

These are the main discoveries I have made in the course of my studies, and I propose to present them in detail on the following pages.

The championship of a heretical point of view is a delicate matter which requires better corroboration than might otherwise be called for. For this reason I have decided to let the dramatis personae speak their own cases as far as possible, and therefore a large part of the following text consists of quotations. This fact does not, of course, guarantee impartiality; against accusations of inequity I can only say that I have done my best. One circumstance which may serve to support this claim is that some persons, above all the principal actor,

Charles Darwin, are quoted to present divergent, even contradictory views.

Before we deal with Darwin’s contribution, we shall first discuss a set of four theories, which in my view are required to account for organic evolution, and some aspects of the history of evolutionary’ thought before Darwin. Subsequently we shall deal with Darwin’s theory, its reception and its fate during the following century. After that follows the presentation of an alternative theory of evolution, which stands up to the problems which have remained unsolved by Darwinism. At this stage, when, in my opinion, the Darwinian myth has been refuted, it may be appropriate to scrutinize it and try to understand why it arose in the first place.

+++++

HT/TC: Darwiniana

Seleção Natural como agente aperfeiçoador

Não obstante os póstumos discípulos de Darwin ignorem o fato taxativamente, é certo que, para este naturalista inglês, o mecanismo de Seleção Natural deveria funcionar como um agente aperfeiçoador do processo evolutivo, atuando pela vida e pela morte, pela sobrevivência do “mais apto” e pela eliminação dos “menos aperfeiçoados”. A Seleção Natural, pois, de certa forma teria às mesmas credenciais de uma divindade onipotente, que, como um exímio oleiro, molda e dar forma à sua arte com extrema habilidade e perfeição. Em todo o livro “A Origem das Espécies”, Darwin faz menção do processo evolucionário como um evento de progressão contínua do “inferior” para o “superior”, do “menos apto” para o “mais apto” e do “imperfeito” para o "verdadeiro modelo de perfeição". Os trechos a seguir, todos extraídos desse referido livro, se não confirmam com perfeição, ao menos apontam com algum primor para esta tese “herética e antidarwinianamente suspeita”.

“Neste caso, ligeiras modificações, favoráveis em qualquer grau que seja aos indivíduos de uma espécie, adaptando-as melhor a novas condições ambientes, tenderiam a perpetuar-se, e a seleção natural teria assim materiais disponíveis para começar a sua obra de aperfeiçoamento” (p. 96).

“Se é vantajoso a uma planta que as suas sementes sejam mais facilmente disseminadas pelo vento, é tão fácil à seleção natural produzir este aperfeiçoamento como é fácil ao agricultor, pela seleção metódica, aumentar e melhorar a penugem contida nas cascas dos seus algodoeiros” (p. 100).

“Enfim, o isolamento assegura a uma nova variedade todo o tempo que lhe é necessário para se aperfeiçoar lentamente, e é este algumas vezes um ponto importante. Contudo, se a região isolada é muito pequena, ou porque seja cercada de barreiras, ou porque as condições físicas sejam todas particulares, o número total dos seus habitantes será também muito pouco considerável, o que retarda a ação da seleção natural, no ponto de vista da seleção de novas espécies, porque as probabilidades da aparição de variedades vantajosas são diminutas" (p.119).

“Depois das alterações físicas, de qualquer natureza, toda a emigração deve ter cessado, de maneira que os antigos habitantes modificados devem ter ocupado todos os novos lugares na economia natural de cada ilha; enfim, o lapso de tempo decorrido permitiu às variedades, que habitavam cada ilha, modificar-se completamente e aperfeiçoar-se. Quando, após os elevamentos, as ilhas se transformaram de novo num continente, uma luta muito viva deve ter recomeçado; as variedades mais favorecidas ou mais aperfeiçoadas puderam então estender-se; as formas menos aperfeiçoadas foram exterminadas, e o continente estaurado mudou de aspecto com respeito ao número relativo dos habitantes. Aí, enfim, abre-se um novo campo à seleção natural, que tende a aperfeiçoar ainda mais os habitantes e a produzir novas espécies” (p.122).

“Resulta daí que as espécies raras se modificam ou se aperfeiçoam menos rapidamente num tempo dado; por conseqüência, são vencidas, na luta pela existência, pelos descendentes modificados ou aperfeiçoados das espécies comuns” (p. 123).

“Os descendentes modificados dos ramos mais recentes e mais aperfeiçoados tendem a tomar o lugar dos ramos mais antigos e menos aperfeiçoados, e por isso a eliminá-los; os ramos inferiores do diagrama, que não chegam até às linhas horizontais superiores, indicam este fato” (p. 132).

“Mas, durante a marcha das modificações, representadas no diagrama, um outro dos nossos princípios, o da extinção, deve ter gozado um papel importante. Como, em cada país bem provido de habitantes, a seleção natural atua necessariamente, dando a uma forma, que faz o objeto da sua ação, algumas vantagens sobre outras formas na luta pela existência, produz-se uma tendência constante entre os descendentes aperfeiçoados de uma espécie qualquer para suplantar e exterminar os seus predecessores e a sua origem primitiva. É preciso lembrar, com efeito, que a luta mais viva se produz ordinariamente entre as formas que estão mais próximas umas das outras, em relação aos hábitos, constituição e estrutura. Por conseqüência, todas as formas intermediárias entre a forma mais antiga e a forma mais moderna, isto é, entre as formas mais ou menos aperfeiçoadas da mesma espécie, assim como a espécie origem própria, tendem ordinariamente a extinguir-se. É provavelmente da mesma maneira para muitas das linhas colaterais completas, vencidas por formas mais recentes e mais aperfeiçoadas" (p. 33).

"As espécies representativas, em número de catorze para a décima quarta geração, têm provavelmente herdado algumas destas vantagens; e são, além disso, modificadas, aperfeiçoadas de diversas maneiras, em cada geração sucessiva, de forma a melhor adaptar-se aos numerosos lugares vagos na economia natural do país que habitam" (p. 34).

"Também a luta para a produção de descendentes novos e modificados se estabelece principalmente entre os grupos mais ricos que tentam multiplicar-se. Um grupo numeroso prevalece sobre um outro grupo considerável, reduzindo-o em número e diminuindo assim as suas probabilidades de variação e aperfeiçoamento. Num mesmo grupo considerável, os subgrupos mais recentes e mais aperfeiçoados, aumentando sem cessar, apoderando-se a cada instante de novos lugares na economia da natureza, tendem constantemente também a suplantar e destruir os subgrupos mais antigos e menos aperfeiçoados. Enfim, os grupos e os subgrupos pouco numerosos e vencidos acabam por desaparecer" (p. 137).

" Cada ser, e é este o ponto final do progresso, tende a aperfeiçoar-se cada vez mais relativamente a estas condições. Este aperfeiçoamento conduz inevitavelmente ao progresso gradual da organização do maior número de seres vivos em todo o mundo. Mas referimo-nos aqui a um assunto muito complicado, porque os naturalistas ainda não definiram, de uma forma satisfatória para todos, o que deve compreender-se por «um progresso de organização». Para os vertebrados, trata-se claramente de um progresso intelectual e de uma conformação que se aproxime da do homem" (p. 138).

"Se adotamos, como critério de uma alta organização, a soma das diferenciações e de especializações dos diversos órgãos em cada indivíduo adulto, o que compreende o aperfeiçoamento intelectual do cérebro, a seleção natural conduz claramente a esse fim" (p. 139).

"Dei o nome de seleção natural a este princípio de conservação ou de persistência do mais apto. Este princípio conduz ao aperfeiçoamento de cada criatura relativamente às condições orgânicas e inorgânicas da sua existência; e, por conseguinte, na maior parte dos casos, ao que podemos considerar como um progresso de organização. Todavia, as formas simples e inferiores persistem muito tempo quando são bem adaptadas às condições pouco complexas da sua existência" (p. 145).

"A seleção natural, como acabamos de fazer observar, conduz à divergência dos caracteres e à extinção completa das formas intermediárias e menos aperfeiçoadas" (p. 146).

"A seleção natural atua apenas pela conservação das modificações vantajosas; cada nova forma, sobrevindo numa localidade suficientemente povoada, tende, por conseqüência, a tomar o lugar da forma primitiva menos aperfeiçoada, ou outras formas menos favorecidas com as quais entra em concorrência, e termina por exterminá-las. Assim, a extinção e a seleção natural vão constantemente de acordo. Por conseguinte, se admitimos que cada espécie descende de alguma força desconhecida, esta, assim como todas as variedades de transição, foram exterminadas pelo fato único da formação e do aperfeiçoamento de uma nova forma" (p. 185).

"Por conseqüência, as formas mais comuns tendem, na luta pela existência, a vencer e a suplantar as formas menos comuns, porque estas últimas modificam-se e aperfeiçoam-se mais lentamente" (p. 189).

"A seleção natural atuando somente pela vida e pela morte, pela persistência do mais apto e pela eliminação dos indivíduos menos aperfeiçoados, experimentei algumas vezes grandes dificuldades para me explicar a origem ou a formação de partes pouco importantes; as dificuldades são tão grandes, neste caso, como quando se trata dos órgãos mais perfeitos e mais complexos, porém são de uma natureza diferente" (p. 214).

"Constituindo o enrolamento o modo mais simples de subir por um suporte e formando a base da nossa série, pode naturalmente perguntar-se como puderam adquirir as plantas esta aptidão nascente, que mais tarde a seleção natural aperfeiçoou e aumentou" (p. 262).

"Não há improbabilidade alguma em acreditar que, nos numerosos insetos, que imitam diversos objetos, uma semelhança acidental com um objeto qualquer foi, em cada caso, o ponto de partida da ação da seleção natural, cujos efeitos deviam aperfeiçoar-se mais tarde pela conservação acidental das variações ligeiras que tendiam a aumentar a semelhança" (p. 265).

"Quando um grande número de habitantes de qualquer região se modifica e aperfeiçoa, resulta do princípio da concorrência e das relações essenciais que têm mutuamente entre si os organismos na luta pela existência, que toda a forma que não se modifica e não se aperfeiçoa em certo grau deve ser exposta à destruição. E dá-se isto porque todas as espécies da mesma região acabam sempre, se se considera um lapso de tempo suficiente longo, por se modificar, porque de outra forma desapareceriam" (p. 383).

"Mas se supusermos a destruição da origem-mãe, o torcaz - e temos toda a razão para acreditar que no estado de natureza as formas pais são geralmente substituídas e exterminadas pelos seus descendentes aperfeiçoados - seria pouco provável que um pombo-pavão, idêntico à raça existente, pudesse derivar da outra espécie de pombo ou mesmo de alguma outra raça bem fixa do pombo doméstico" (p. 384).

"Temos, até ao presente, falado apenas incidentemente do desaparecimento das espécies e dos grupos de espécies. Pela teoria da seleção natural, a extinção das formas antigas e a produção das formas novas aperfeiçoadas são dois fatos intimamente conexos" (p. 385).

"A concorrência é geralmente mais rigorosa, como com exemplos o demonstramos já, entre as formas que se semelham em todos os pontos de vista. Por conseguinte, os descendentes modificados e aperfeiçoados de uma espécie causam geralmente o extermínio da origem-mãe; e se muitas novas formas, provindo de uma mesma espécie, conseguem desenvolver-se, são as formas mais próximas desta espécie, isto é, as espécies do mesmo gênero, que se encontram mais expostas à destruição" (p. 389).

"As espécies antigas, vencidas pelas novas formas vitoriosas, às quais cedem o lugar, são geralmente aliadas em grupos, conseqüência da herança comum de alguma causa de inferioridade; à medida pois que os grupos novos e aperfeiçoados se espalham na Terra, os antigos desaparecem, e por toda a parte há correspondência na sucessão das formas, tanto na sua primeira aparição como no desaparecimento final" (p. 393).

"Vimos, no quarto capítulo, que, em todos os seres organizados que atingiram a idade adulta, o grau de diferenciação e de especialização dos diversos órgãos nos permite determinar o grau de aperfeiçoamento e superioridade relativa. Vimos também que, a especialização dos órgãos constituindo uma vantagem para cada ser, deve a seleção natural tender a especializar a organização de cada indivíduo, e a torná-la, em tal ponto de vista, mais perfeita e mais elevada" (p. 402).

"Parece-me, por outro lado, que todas as leis essenciais estabelecidas pela paleontologia proclamam claramente que as espécies são o produto da geração ordinária, e que as formas antigas foram substituídas por formas novas e aperfeiçoadas, e elas mesmo o resultado da variação e da persistência do mais apto" (p. 412).

"Demonstrei também que as variedades intermediárias, que têm provavelmente ocupado a princípio zonas intermediárias, devem ter sido suplantadas por formas aliadas existindo de uma parte e de outra; porque estas últimas, sendo as mais numerosas, tendem, por esta razão mesmo, a modificar-se e a aperfeiçoar-se mais rapidamente que as espécies intermediárias menos abundantes; de modo que estas devem ter sido, há muito, exterminadas e substituídas" (p. 527).

"As variedades novas e aperfeiçoadas devem substituir e exterminar, inevitavelmente, as variedades mais antigas, intermediárias e menos perfeitas, e as espécies tendem a tornar-se assim mais distintas e melhor definidas. As espécies dominantes, que fazem parte dos grupos principais de cada classe, tendem a dar origem a formas novas e dominantes, e cada grupo principal tende sempre também a crescer cada vez mais, e ao mesmo tempo, a apresentar caracteres sempre mais divergentes" (p. 534).

"A extinção das espécies e de grupos completos de espécies, que tem gozado um papel tão considerável na história do mundo orgânico, é a conseqüência inevitável da seleção natural; porque as formas antigas devem ser suplantadas pelas formas novas e aperfeiçoadas" (p. 539).

"Consideram-se as formas novas como sendo, em conjunto, geralmente mais elevadas na escala da organização do que as formas antigas; devem-no ser, além disso, porque são as formas mais recentes e mais aperfeiçoadas que, na luta pela existência, têm devido sobrepujar as formas mais antigas e menos perfeitas; os seus órgãos devem ter-se também especializado muito para desempenhar as suas diversas funções" (p. 540).

"Como a produção e a extinção das espécies são a conseqüência das causas sempre existentes e atuando lentamente, e não por atos miraculosos de criação; como a mais importante das causas das alterações orgânicas é quase independente de toda a modificação, mesmo súbita, nas condições físicas, porque esta causa não é mais que as relações mútuas de organismo para organismo, o aperfeiçoamento de um arrastando o aperfeiçoamento ou o extermínio de outros, resulta que a soma das modificações orgânicas apreciáveis nos fósseis de formações consecutivas pode provavelmente servir de medida relativa, mas não absoluta, do lapso de tempo decorrido entre o depósito de cada uma delas. Estas leis, tomadas no seu sentido mais lato, são: a lei do crescimento e reprodução; a lei da hereditariedade que implica quase a lei de reprodução; a lei de variabilidade, resultante da ação direta e indireta das condições de existência, do uso e não uso; a lei da multiplicação das espécies em razão bastante elevada para trazer a luta pela existência, que tem como conseqüência a seleção natural, que determina a divergência de caracteres, a extinção de formas menos aperfeiçoadas. O resultado direto desta guerra da natureza que se traduz pela fome e pela morte, é, pois, o fato mais admirável que podemos conceber, a saber: a produção de animais superiores. Não há uma verdadeira grandeza nesta forma de considerar a vida, com os seus poderes diversos atribuídos primitivamente pelo Criador a um pequeno número de formas, ou mesmo a uma só? Ora, enquanto que o nosso planeta, obedecendo à lei fixa da gravitação, continua a girar na sua órbita, uma quantidade infinita de belas e admiráveis formas, saídas de um começo tão simples, não têm cessado de se desenvolver e desenvolvem-se ainda!" (p. 553, 554).

Fonte:

Charles Darwin: "A Origem das Espécies, no meio da seleção natural ou a luta pela existência na natureza". Tradução: Joaquim da Mesquita Paul. Lello & Irmãos Editores. Porto, 2003.

É isso!

Não obstante os póstumos discípulos de Darwin ignorem o fato taxativamente, é certo que, para este naturalista inglês, o mecanismo de Seleção Natural deveria funcionar como um agente aperfeiçoador do processo evolutivo, atuando pela vida e pela morte, pela sobrevivência do “mais apto” e pela eliminação dos “menos aperfeiçoados”. A Seleção Natural, pois, de certa forma teria às mesmas credenciais de uma divindade onipotente, que, como um exímio oleiro, molda e dar forma à sua arte com extrema habilidade e perfeição. Em todo o livro “A Origem das Espécies”, Darwin faz menção do processo evolucionário como um evento de progressão contínua do “inferior” para o “superior”, do “menos apto” para o “mais apto” e do “imperfeito” para o "verdadeiro modelo de perfeição". Os trechos a seguir, todos extraídos desse referido livro, se não confirmam com perfeição, ao menos apontam com algum primor para esta tese “herética e antidarwinianamente suspeita”.

“Neste caso, ligeiras modificações, favoráveis em qualquer grau que seja aos indivíduos de uma espécie, adaptando-as melhor a novas condições ambientes, tenderiam a perpetuar-se, e a seleção natural teria assim materiais disponíveis para começar a sua obra de aperfeiçoamento” (p. 96).

“Se é vantajoso a uma planta que as suas sementes sejam mais facilmente disseminadas pelo vento, é tão fácil à seleção natural produzir este aperfeiçoamento como é fácil ao agricultor, pela seleção metódica, aumentar e melhorar a penugem contida nas cascas dos seus algodoeiros” (p. 100).

“Enfim, o isolamento assegura a uma nova variedade todo o tempo que lhe é necessário para se aperfeiçoar lentamente, e é este algumas vezes um ponto importante. Contudo, se a região isolada é muito pequena, ou porque seja cercada de barreiras, ou porque as condições físicas sejam todas particulares, o número total dos seus habitantes será também muito pouco considerável, o que retarda a ação da seleção natural, no ponto de vista da seleção de novas espécies, porque as probabilidades da aparição de variedades vantajosas são diminutas" (p.119).

“Depois das alterações físicas, de qualquer natureza, toda a emigração deve ter cessado, de maneira que os antigos habitantes modificados devem ter ocupado todos os novos lugares na economia natural de cada ilha; enfim, o lapso de tempo decorrido permitiu às variedades, que habitavam cada ilha, modificar-se completamente e aperfeiçoar-se. Quando, após os elevamentos, as ilhas se transformaram de novo num continente, uma luta muito viva deve ter recomeçado; as variedades mais favorecidas ou mais aperfeiçoadas puderam então estender-se; as formas menos aperfeiçoadas foram exterminadas, e o continente estaurado mudou de aspecto com respeito ao número relativo dos habitantes. Aí, enfim, abre-se um novo campo à seleção natural, que tende a aperfeiçoar ainda mais os habitantes e a produzir novas espécies” (p.122).

“Resulta daí que as espécies raras se modificam ou se aperfeiçoam menos rapidamente num tempo dado; por conseqüência, são vencidas, na luta pela existência, pelos descendentes modificados ou aperfeiçoados das espécies comuns” (p. 123).

“Os descendentes modificados dos ramos mais recentes e mais aperfeiçoados tendem a tomar o lugar dos ramos mais antigos e menos aperfeiçoados, e por isso a eliminá-los; os ramos inferiores do diagrama, que não chegam até às linhas horizontais superiores, indicam este fato” (p. 132).

“Mas, durante a marcha das modificações, representadas no diagrama, um outro dos nossos princípios, o da extinção, deve ter gozado um papel importante. Como, em cada país bem provido de habitantes, a seleção natural atua necessariamente, dando a uma forma, que faz o objeto da sua ação, algumas vantagens sobre outras formas na luta pela existência, produz-se uma tendência constante entre os descendentes aperfeiçoados de uma espécie qualquer para suplantar e exterminar os seus predecessores e a sua origem primitiva. É preciso lembrar, com efeito, que a luta mais viva se produz ordinariamente entre as formas que estão mais próximas umas das outras, em relação aos hábitos, constituição e estrutura. Por conseqüência, todas as formas intermediárias entre a forma mais antiga e a forma mais moderna, isto é, entre as formas mais ou menos aperfeiçoadas da mesma espécie, assim como a espécie origem própria, tendem ordinariamente a extinguir-se. É provavelmente da mesma maneira para muitas das linhas colaterais completas, vencidas por formas mais recentes e mais aperfeiçoadas" (p. 33).

"As espécies representativas, em número de catorze para a décima quarta geração, têm provavelmente herdado algumas destas vantagens; e são, além disso, modificadas, aperfeiçoadas de diversas maneiras, em cada geração sucessiva, de forma a melhor adaptar-se aos numerosos lugares vagos na economia natural do país que habitam" (p. 34).

"Também a luta para a produção de descendentes novos e modificados se estabelece principalmente entre os grupos mais ricos que tentam multiplicar-se. Um grupo numeroso prevalece sobre um outro grupo considerável, reduzindo-o em número e diminuindo assim as suas probabilidades de variação e aperfeiçoamento. Num mesmo grupo considerável, os subgrupos mais recentes e mais aperfeiçoados, aumentando sem cessar, apoderando-se a cada instante de novos lugares na economia da natureza, tendem constantemente também a suplantar e destruir os subgrupos mais antigos e menos aperfeiçoados. Enfim, os grupos e os subgrupos pouco numerosos e vencidos acabam por desaparecer" (p. 137).

" Cada ser, e é este o ponto final do progresso, tende a aperfeiçoar-se cada vez mais relativamente a estas condições. Este aperfeiçoamento conduz inevitavelmente ao progresso gradual da organização do maior número de seres vivos em todo o mundo. Mas referimo-nos aqui a um assunto muito complicado, porque os naturalistas ainda não definiram, de uma forma satisfatória para todos, o que deve compreender-se por «um progresso de organização». Para os vertebrados, trata-se claramente de um progresso intelectual e de uma conformação que se aproxime da do homem" (p. 138).

"Se adotamos, como critério de uma alta organização, a soma das diferenciações e de especializações dos diversos órgãos em cada indivíduo adulto, o que compreende o aperfeiçoamento intelectual do cérebro, a seleção natural conduz claramente a esse fim" (p. 139).

"Dei o nome de seleção natural a este princípio de conservação ou de persistência do mais apto. Este princípio conduz ao aperfeiçoamento de cada criatura relativamente às condições orgânicas e inorgânicas da sua existência; e, por conseguinte, na maior parte dos casos, ao que podemos considerar como um progresso de organização. Todavia, as formas simples e inferiores persistem muito tempo quando são bem adaptadas às condições pouco complexas da sua existência" (p. 145).

"A seleção natural, como acabamos de fazer observar, conduz à divergência dos caracteres e à extinção completa das formas intermediárias e menos aperfeiçoadas" (p. 146).

"A seleção natural atua apenas pela conservação das modificações vantajosas; cada nova forma, sobrevindo numa localidade suficientemente povoada, tende, por conseqüência, a tomar o lugar da forma primitiva menos aperfeiçoada, ou outras formas menos favorecidas com as quais entra em concorrência, e termina por exterminá-las. Assim, a extinção e a seleção natural vão constantemente de acordo. Por conseguinte, se admitimos que cada espécie descende de alguma força desconhecida, esta, assim como todas as variedades de transição, foram exterminadas pelo fato único da formação e do aperfeiçoamento de uma nova forma" (p. 185).

"Por conseqüência, as formas mais comuns tendem, na luta pela existência, a vencer e a suplantar as formas menos comuns, porque estas últimas modificam-se e aperfeiçoam-se mais lentamente" (p. 189).

"A seleção natural atuando somente pela vida e pela morte, pela persistência do mais apto e pela eliminação dos indivíduos menos aperfeiçoados, experimentei algumas vezes grandes dificuldades para me explicar a origem ou a formação de partes pouco importantes; as dificuldades são tão grandes, neste caso, como quando se trata dos órgãos mais perfeitos e mais complexos, porém são de uma natureza diferente" (p. 214).

"Constituindo o enrolamento o modo mais simples de subir por um suporte e formando a base da nossa série, pode naturalmente perguntar-se como puderam adquirir as plantas esta aptidão nascente, que mais tarde a seleção natural aperfeiçoou e aumentou" (p. 262).

"Não há improbabilidade alguma em acreditar que, nos numerosos insetos, que imitam diversos objetos, uma semelhança acidental com um objeto qualquer foi, em cada caso, o ponto de partida da ação da seleção natural, cujos efeitos deviam aperfeiçoar-se mais tarde pela conservação acidental das variações ligeiras que tendiam a aumentar a semelhança" (p. 265).

"Quando um grande número de habitantes de qualquer região se modifica e aperfeiçoa, resulta do princípio da concorrência e das relações essenciais que têm mutuamente entre si os organismos na luta pela existência, que toda a forma que não se modifica e não se aperfeiçoa em certo grau deve ser exposta à destruição. E dá-se isto porque todas as espécies da mesma região acabam sempre, se se considera um lapso de tempo suficiente longo, por se modificar, porque de outra forma desapareceriam" (p. 383).

"Mas se supusermos a destruição da origem-mãe, o torcaz - e temos toda a razão para acreditar que no estado de natureza as formas pais são geralmente substituídas e exterminadas pelos seus descendentes aperfeiçoados - seria pouco provável que um pombo-pavão, idêntico à raça existente, pudesse derivar da outra espécie de pombo ou mesmo de alguma outra raça bem fixa do pombo doméstico" (p. 384).

"Temos, até ao presente, falado apenas incidentemente do desaparecimento das espécies e dos grupos de espécies. Pela teoria da seleção natural, a extinção das formas antigas e a produção das formas novas aperfeiçoadas são dois fatos intimamente conexos" (p. 385).

"A concorrência é geralmente mais rigorosa, como com exemplos o demonstramos já, entre as formas que se semelham em todos os pontos de vista. Por conseguinte, os descendentes modificados e aperfeiçoados de uma espécie causam geralmente o extermínio da origem-mãe; e se muitas novas formas, provindo de uma mesma espécie, conseguem desenvolver-se, são as formas mais próximas desta espécie, isto é, as espécies do mesmo gênero, que se encontram mais expostas à destruição" (p. 389).

"As espécies antigas, vencidas pelas novas formas vitoriosas, às quais cedem o lugar, são geralmente aliadas em grupos, conseqüência da herança comum de alguma causa de inferioridade; à medida pois que os grupos novos e aperfeiçoados se espalham na Terra, os antigos desaparecem, e por toda a parte há correspondência na sucessão das formas, tanto na sua primeira aparição como no desaparecimento final" (p. 393).

"Vimos, no quarto capítulo, que, em todos os seres organizados que atingiram a idade adulta, o grau de diferenciação e de especialização dos diversos órgãos nos permite determinar o grau de aperfeiçoamento e superioridade relativa. Vimos também que, a especialização dos órgãos constituindo uma vantagem para cada ser, deve a seleção natural tender a especializar a organização de cada indivíduo, e a torná-la, em tal ponto de vista, mais perfeita e mais elevada" (p. 402).

"Parece-me, por outro lado, que todas as leis essenciais estabelecidas pela paleontologia proclamam claramente que as espécies são o produto da geração ordinária, e que as formas antigas foram substituídas por formas novas e aperfeiçoadas, e elas mesmo o resultado da variação e da persistência do mais apto" (p. 412).

"Demonstrei também que as variedades intermediárias, que têm provavelmente ocupado a princípio zonas intermediárias, devem ter sido suplantadas por formas aliadas existindo de uma parte e de outra; porque estas últimas, sendo as mais numerosas, tendem, por esta razão mesmo, a modificar-se e a aperfeiçoar-se mais rapidamente que as espécies intermediárias menos abundantes; de modo que estas devem ter sido, há muito, exterminadas e substituídas" (p. 527).

"As variedades novas e aperfeiçoadas devem substituir e exterminar, inevitavelmente, as variedades mais antigas, intermediárias e menos perfeitas, e as espécies tendem a tornar-se assim mais distintas e melhor definidas. As espécies dominantes, que fazem parte dos grupos principais de cada classe, tendem a dar origem a formas novas e dominantes, e cada grupo principal tende sempre também a crescer cada vez mais, e ao mesmo tempo, a apresentar caracteres sempre mais divergentes" (p. 534).

"A extinção das espécies e de grupos completos de espécies, que tem gozado um papel tão considerável na história do mundo orgânico, é a conseqüência inevitável da seleção natural; porque as formas antigas devem ser suplantadas pelas formas novas e aperfeiçoadas" (p. 539).

"Consideram-se as formas novas como sendo, em conjunto, geralmente mais elevadas na escala da organização do que as formas antigas; devem-no ser, além disso, porque são as formas mais recentes e mais aperfeiçoadas que, na luta pela existência, têm devido sobrepujar as formas mais antigas e menos perfeitas; os seus órgãos devem ter-se também especializado muito para desempenhar as suas diversas funções" (p. 540).