Últimos assuntos

Tópicos mais visitados

Tópicos mais ativos

A árvore da vida de Darwin

Página 1 de 1

15022010

A árvore da vida de Darwin

A árvore da vida de Darwin

A Árvore da Vida de Darwin está errada e induz ao erro

Charles Darwin's tree of life is 'wrong and misleading', claim scientists

Charles Darwin's tree of life, which shows how species are related, is " wrong" and "misleading", claim scientists.

Charles Darwin's idea of a tree of life is now 'obsolete' according to some scientists

Photo: ENGLISH HERITAGE PHOTO LIBRARY

Photo: ENGLISH HERITAGE PHOTO LIBRARY

They believe the concept misleads us because his theory limits and even obscures the study of organisms and their ancestries.

Evolution is far too complex to be explained by a few roots and branches, they claim.

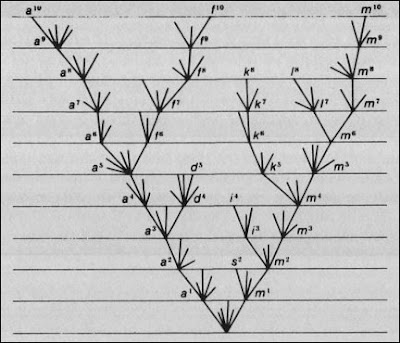

In Darwin's The Origin of Species, published in 1859, the British naturalist drew a diagram of an oak to depict how one species can evolve into many.

But not much was known about primitive life forms or genetics back then when he was only dealing with plants and animals – long before there was any real comprehension of DNA or bacteria.

Researchers say although for much of the past 150 years biology has largely concerned itself with filling in the details of the tree it is now obsolete and needs to be discarded.

Dr Eric Bapteste, an evolutionary biologist at the Pierre and Marie Curie University in Paris, said: "For a long time the holy grail was to build a tree of life. We have no evidence at all that the tree of life is a reality."

The discovery of the structure of DNA in 1953 – whose pioneers believed it would provide proof of Darwin's tree – opened up new vistas for evolutionary biology.

But current research is finding a far more complex scenario than Darwin could have imagined – particularly in relation to bacteria and single-celled organisms.

These simple life forms represent most of Earth's biomass and diversity – not to mention the first two-thirds of the planet's history.

Many of their species swap genes back and forth, or engage in gene duplication, recombination, gene loss or gene transfers from multiple sources.

Dr John Dupré, a philosopher of biology at Exeter University, said: "If there is a tree of life it's a small irregular structure growing out of the web of life."

More fundamentally recent research suggests the evolution of animals and plants isn't exactly tree-like either.

Dr Dupré said: "There are problems even in that little corner." Having uprooted the tree of unicellular life biologists are now taking their axes to the remaining branches.

...

Read more here/Leia mais aqui: The Telegraph

+++++

NOTA IMPERTINENTE DESTE BLOGGER:

Eu fui evolucionista de carteirinha, e disse adeus a Darwin, sem medo de ser feliz, após a leitura do livro A Caixa Preta de Darwin, de Michael Behe (1997, Rio de Janeiro, Zahar): a bioquímica detona as especulações transformistas de Darwin.

Posições esdrúxulas da Nomenklatura científica (autoritária e medieval nas práticas contra os oponentes), da Grande Mídia Tupiniquim (acapachante amante silenciosa) e a Galera dos meninos e meninas de Darwin (histérica por se ver órfã epistêmica): silêncio pétreo sobre estas dificuldades teóricas fundamentais para a corroboração de uma teoria científica no contexto de justificação teórica.

Posição mais esdrúxula ainda é a do MEC/SEMTEC/PNLEM que, despudoramente, apesar de ter recebido análise crítica dessas questões em 2003 e 2005 (tenho comprovante de recepção) aprova livros didáticos de Biologia do ensino médio com duas fraudes e várias evidências científicas distorcidas a favor do fato, Fato, FATO da evolução.

Gente, alguém me belisque, mas o que deve ser feito para ver o direito de cidadania em se ter acesso às informações científicas atuais e desmotivadas da ideologia do materialismo filosófico sendo discutidas pública e abertamente nas salas de aulas de ciência, nas universidades e em outros espaços acadêmicos?

Fui, nem sei por que, pensando: Quando a questão é Darwin, o ídolo secular, é tutti cosi nostra, capice? Capice???

[/b]

Doolittle arranca pela raiz a Árvore da Vida de Darwin

Uprooting Tree of Life

About 10 years ago scientists finally worked out the basic outline of how modern life-forms evolved. Now parts of their tidy scheme are unraveling

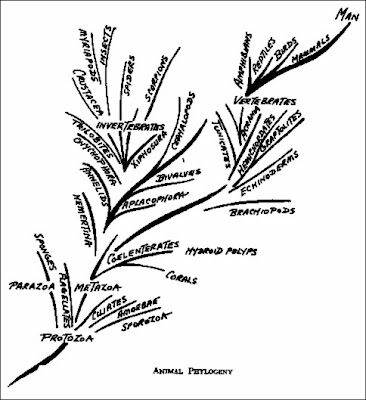

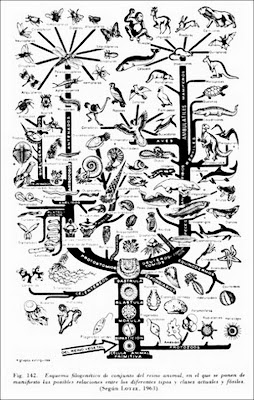

Charles Darwin contended more than a century ago that all modern species diverged from a more limited set of ancestral groups, which themselves evolved from still fewer progenitors and so on back to the beginning of life. In principle, then, the relationships among all living and extinct organisms could be represented as a single genealogical tree.

Most contemporary researchers agree. Many would even argue that the general features of this tree are already known, all the way down to the root—a solitary cell, termed life’s last universal common ancestor, that lived roughly 3.5 to 3.8 billion years ago. The consensus view did not come easily but has been widely accepted for more than a decade.

Yet ill winds are blowing. To everyone’s surprise, discoveries made in the past few years have begun to cast serious doubt on some aspects of the tree, especially on the depiction of the relationships near the root.

The First Sketches

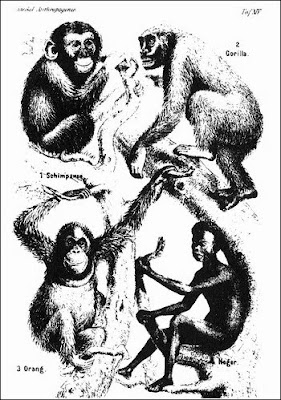

Scientists could not even begin to contemplate constructing a universal tree until about 35 years ago. From the time of Aristotle to the 1960s, researchers deduced the relatedness of organisms by comparing their anatomy or physiology, or both. For complex organisms, they were frequently able to draw reasonable genealogical inferences in this way. Detailed analyses of innumerable traits suggested, for instance, that hominids shared a common ancestor with apes, that this common ancestor shared an earlier one with monkeys, and that that precursor shared an even earlier forebear with prosimians, and so forth.

Microscopic single-celled organisms, however, often provided too little information for defining relationships. That paucity was disturbing because microbes were the only inhabitants of the earth for the first half to two thirds of the planet’s history; the absence of a clear phylogeny (family tree) for microorganisms left scientists unsure about the sequence in which some of the most radical innovations in cellular structure and function occurred. For example, between the birth of the first cell and the appearance of multicellular fungi, plants and animals, cells grew bigger and more complex, gained a nucleus and a cytoskeleton (internal scaffolding), and found a way to eat other cells. In the mid-1960s Emile Zuckerkandl and Linus Pauling of the California Institute of Technology conceived of a revolutionary strategy that could supply the missing information.

...

FULL PDF FREE/PDF COMPLETO GRÁTIS

A árvore da vida de 1%

The tree of one percent

Tal Dagan and William Martin

Institute of Botany, University of Düsseldorf, D-40225 Düsseldorf, Germany

author email corresponding author email

Genome Biology 2006, 7:118doi:10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-118

Subject areas: Evolution, Microbiology and parasitology, Genome studies

The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found online at: http://genomebiology.com/2006/7/10/118

Published: 1 November 2006

© 2006 BioMed Central Ltd

Abstract

Two significant evolutionary processes are fundamentally not tree-like in nature - lateral gene transfer among prokaryotes and endosymbiotic gene transfer (from organelles) among eukaryotes. To incorporate such processes into the bigger picture of early evolution, biologists need to depart from the preconceived notion that all genomes are related by a single bifurcating tree.

Opinion

Evolutionary biologists like to think in terms of trees. Since Darwin, biologists have envisaged phylogeny as a tree-like process of lineage splittings. But Darwin was not concerned with the evolution of microbes, where lateral gene transfer (LGT; a distinctly non-treelike process) is an important mechanism of natural variation, as prokaryotic genome sequences attest [1-4]. Evolutionary biologists are not debating whether LGT exists. But they are debating - and heatedly so - how much LGT actually goes on in evolution. Recent estimates of the proportion of prokaryotic genes that have been affected by LGT differ 30-fold, ranging from 2% [5] to 60% [6]. Biologists are also hotly debating how LGT should influence our approach to understanding genome evolution on the one hand, and our approach to the natural classification of all living things on the other. These debates erupt most acutely over the concept of a tree of life. Here we consider how LGT and endosymbiosis bear on contemporary views of microbial evolution, most of which stem from the days before genome sequences were available.

A tree of life?

When it comes to the concept of a tree of life, there are currently two main camps. One camp, which we shall call the positivists, says that there is a tree of life, that microbial genomes are, in the main, related by a series of bifurcations, and that when we have sifted out a presumably small amount of annoying chaff (LGT), the wheat (the tree) will be there and will still our hunger for a grand and natural system [7-10]. The other camp, which we will call the microbialists, says that LGT is just as natural among prokaryotes as is point mutation, and that furthermore, it has occurred throughout microbial history. This means that even were we to agree on a grand natural classification, the process of microbial evolution underlying it would be fundamentally undepictable as a single bifurcating tree, because a substantial component of the evolutionary process - LGT - is not tree-like to begin with [1,11,12].

A recent paper by Ciccarelli et al. [9] brings these two views head-to-head. It purports to weigh in heavily for the positivists, but in doing so it inadvertently provides some of the strongest support for the microbialist camp that has been published so far. A closer look reveals why. Ciccarelli et al. [9] report an automated procedure for identifying protein families that are universally distributed among all genomes, with pipeline alignment and tree building. Their routine looked for possible cases of LGT (detected as unusual tree topologies), excluded such proteins, and reiterated the procedure until the universe of proteins had been examined. This left them with 31 presumably orthologous protein sequences present in 191 genomes each, the alignments of which were concatenated to produce a data matrix with 8,089 sites (of which only 1,212 would have remained had gapped sites been excluded). A maximum likelihood tree was inferred from this matrix, motivating a brief discussion of some important events in life's history as inferred from that tree.

Fair enough, one might say, what is there to debate? Lots. Bearing in mind that an average prokaryotic proteome represents about 3,000 protein-coding genes, the 31-protein tree of life represents only about 1% of an average prokaryotic proteome and only 0.1% of a large eukaryotic proteome. Thus, the positivists can say that there is a tree of life after all: a bit skimpier than expected, but a tree nonetheless. But the microbialists, glaring at the same data, can say that the glass is only 1% full at best, and more than 99% empty! There might be a tree there, but it is not the tree of life, it is the 'tree of one percent of life'.

Looking at the issue openly, the finding that, on average, only 0.1% to 1% of each genome fits the metaphor of a tree of life overwhelmingly supports the central pillar of the microbialist argument that a single bifurcating tree is an insufficient model to describe the microbial evolutionary process. If throwing out all non-universally distributed genes and all suspected cases of LGT in our search for the tree of life leaves us with a tree of one percent, then we should probably abandon the tree as a working hypothesis. When chemists or physicists find that a given null hypothesis can account for only 1% of their data, they immediately start searching for a better hypothesis. Not so with microbial evolution, it seems, which is rather worrying. Could it be that many biologists have their heart set on finding a tree of life, regardless of what the data actually say?

+++++

FREE PDF GRÁTIS [OPEN ACCESS]

+++++

Gente, Árvore da Vida de 1%? Darwin, todo mundo pensou que você tinha ilustrado sua Árvore da Vida com todo o cuidado de um pesquisador meticuloso como você que levou uns 20 anos para publicar sua teoria para não chocar os pruridos da Igreja Anglicana, e agora ela não rende mais do que míseros 1% de evidência?

E a Nomenklatura científica tem a cara de pau de dizer que o fato, Fato, FATO da evolução é um fato científico tão comprovado como a lei da gravidade. A lei da gravidade é um fenômeno científico 100% comprovado, mas o que dizer de uma árvore da vida com apenas 1% de evidência? Eu, se ainda fosse darwinista, não usaria mais esta retórica ufanista e em descompasso com a verdade das evidências.

Fui, nem sei por que, pensando no pesadelo que a Nomenklatura científica vem tendo desde 1859: as hipóteses transformistas de Darwin (um Australopithecus afarensis se transformar em Antropólogo amazonense) não são corroboradas em um contexto de justificação teórica.

O fato, Fato, FATO da evolução é uma verdade científica aceita a priori: um mero axioma.

A cada vez mais confusa árvore da vida evolucionista

João 1:3

Todas as coisas foram feitas por Ele, e, sem Ele, nada do que foi feito se fez.

Pesquisadores a estudar a genética concluíram que a árvore da vida evolutiva não corresponde aos factos da bioquímica.

Desde os anos 60 que os bioquímicos concluíram que os seres vivos poderiam ser agrupados em dois tipos distintos tendo como base a estrutura nuclear e a informação genética. Eucariotas tem uma ou mais células e um verdadeiro núcleo. Procariotas possuem células mais pequenas sem um núcleo. Estas últimas são tão distintas das eucariotas que os evolucionistas concluíram que elas devem-se ter desenvolvido separadamente uma da outra.

No final dos anos 70 um outro tipo foi reconhecido: as arqueas. As arqueas preferem ambientes mais extremos como passagens subaquáticas.Obrigado pelo comentário. Comunicar outra imagemComunique a imagem ofensiva. CancelarConcluído

A sua bioquímica é totalmente distinta da bioquímica dos eucariotas e das procariotas. De acordo com os evolucionistas a vida pode-se ter desenvolvido a partir da matéria inanimada 3 vezes distintas. Para além disso, como forma de explicar a bioquímica destes 3 tipos de criatura, os bioquímicos evolucionistas tem que assumir que, pontualmente, estes tipos separados tiveram que trocar material genético uns com os outros, bem como com uma quarta forma de vida, ainda desconhecida.

Uma conclusão lógica desta nova visão evolucionista é que a vida tem que ter emergido muitas vezes a partir de matéria morta, no entanto a bioquímica moderna ainda não conseguiu explicar como é que a vida surgiu da matéria morta apenas uma única vez. Se calhar não era má ideia começar-se por aí e depois avançar para as outras duas.

O óbvio insucesso do naturalismo para explicar a origem da vida não é algo marginal no debate Darwin vs Design. A teoria da evolução é a versão naturalista da origem e diversificação da vida, e como tal se esse mesmo naturalismo não é suficiente para explicar como é que a vida começou, porque é que se vai assumir que a diversificação dessa mesma vida (e o aparecimento de novos órgãos e novas células) é algo que tem que se explicado dentro do âmbito do mesmo naturalismo?

O que os ateus não querem aceitar (embora já se tenham apercebido disso) é que a teoria da evolução falha pelas mesmas razões que a versão naturalista da origem da vida falha: não há força não inteligente capaz de organizar a matéria morta de modo a que ela possa fazer aquilo que as formas de vida fazem. Enquanto os ateus estiverem ideologicamente presos ao naturalismo, eles nunca vão aceitar o que a ciência e a Bíblia em união mostram sobre a origem da vida.

O padrão da vida, por outro lado, é algo que claramente se esperaria se ela tivesse sido o resultado do Criador Infinitamente Sábio que usou design semelhante para resolver problemas semelhantes.Referências: Scientific American, 2/00, pp. 90-95, "Uprooting the Tree of Life"

Darwin disse, mas nunca explicou cientificamente a contento sobre a origem das espécies

Quinta-feira, Março 11, 2010

New Scientist

Accidental origins: Where species come from

10 March 2010 by Bob Holmes

Magazine issue 2751.

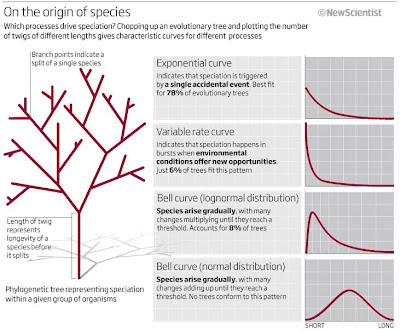

ANTARCTIC fish deploy antifreeze proteins to survive in cold water. Tasty viceroy butterflies escape predators by looking like toxic monarchs. Disease-causing bacteria become resistant to antibiotics. Everywhere you look in nature, you can see evidence of natural selection at work in the adaptation of species to their environment. Surprisingly though, natural selection may have little role to play in one of the key steps of evolution - the origin of new species. Instead it would appear that speciation is merely an accident of fate.

So, at least, says Mark Pagel, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Reading, UK. If his controversial claim proves correct, then the broad canvas of life - the profusion of beetles and rodents, the dearth of primates, and so on - may have less to do with the guiding hand of natural selection and more to do with evolutionary accident-proneness.

Of course, there is no question that natural selection plays a key role in evolution. [SIC ULTRA PLUS] Darwin made a convincing case a century and a half ago in On the Origin of Species, and countless subsequent studies support his ideas [???]. But there is an irony in Darwin's choice of title: his book did not explore what actually triggers the formation of a new species. Others have since grappled with the problem of how one species becomes two, and with the benefit of genetic insight, which Darwin lacked, you might think they would have cracked it. Not so. Speciation still remains one of the biggest mysteries in evolutionary biology.

Even defining terms is not straightforward. Most biologists see a species as a group of organisms that can breed among themselves but not with other groups. There are plenty of exceptions to that definition - as with almost everything in biology - but it works pretty well most of the time. In particular, it focuses attention on an important feature of speciation: for one species to become two, some subset of the original species must become unable to reproduce with its fellows.

How this happens is the real point of contention. By the middle of the 20th century, biologists had worked out that reproductive isolation sometimes occurs after a few organisms are carried to newly formed lakes or far-off islands. Other speciation events seem to result from major changes in chromosomes, which suddenly leave some individuals unable to mate successfully with their neighbours.

It seems unlikely, though, that such drastic changes alone can account for all or even most new species, and that's where natural selection comes in. Species exist as more or less separate populations in different areas, and the idea here is that two populations may gradually drift apart, like old friends who no longer take the time to talk, as each adapts to a different set of local conditions. "I think the unexamined view that most people have of speciation is this gradual accumulation by natural selection of a whole lot of changes, until you get a group of individuals that can no longer mate with their old population," says Pagel.

Until now, no one had found a way to test whether this hunch really does account for the bulk of speciation events, but more than a decade ago Pagel came up with an idea of how to solve this problem. If new species are the sum of a large number of small changes, he reasoned, then this should leave a telltale statistical footprint in their evolutionary lineage.

Whenever a large number of small factors combine to produce an outcome - whether it be a combination of nature and nurture determining an individual's height, economic forces setting stock prices, or the vagaries of weather dictating daily temperatures - a big enough sample of such outcomes tends to produce the familiar bell-shaped curve that statisticians call a normal distribution. For example, people's height varies widely, but most heights are clustered around the middle values. So, if speciation is the result of many small evolutionary changes, Pagel realised, then the time interval between successive speciation events - that is, the length of each branch in an evolutionary tree - should also fit a bell-shaped distribution (see diagram). That insight, straightforward as it was, ran into a roadblock, however: there simply weren't enough good evolutionary trees to get an accurate statistical measure of the branch lengths. So Pagel filed his idea away and got on with other things.

Then, a few years ago, he realised that reliable trees had suddenly become abundant, thanks to cheap and speedy DNA sequencing technology. "For the first time, we have a large tranche of really good phylogenetic trees to test the idea," he says. So he and his colleagues Chris Venditti and Andrew Meade rolled up their sleeves and got stuck in.

The team gleaned more than 130 DNA-based evolutionary trees from the published literature, ranging widely across plants, animals and fungi. After winnowing the list to exclude those of questionable accuracy, they ended up with a list of 101 trees, including various cats, bumblebees, hawks, roses and the like.

Working with each tree separately, they measured the length between each successive speciation event, essentially chopping the tree into its component twigs at every fork. Then they counted up the number of twigs of each length, and looked to see what pattern this made. If speciation results from natural selection via many small changes, you would expect the branch lengths to fit a bell-shaped curve. This would take the form of either a normal curve if the incremental changes sum up to push the new species over some threshold of incompatibility, or the related lognormal curve if the changes multiply together, compounding one another to reach the threshold more quickly.

To their surprise, neither of these curves fitted the data. The lognormal was best in only 8 per cent of cases, and the normal distribution failed resoundingly, providing the best explanation for not a single evolutionary tree. Instead, Pagel's team found that in 78 per cent of the trees, the best fit for the branch length distribution was another familiar curve, known as the exponential distribution (Nature, DOI: 10.1038/nature08630).

...

Read more here/Leia mais aqui: New Scientist

+++++

Nature 463, 349-352 (21 January 2010) | doi:10.1038/nature08630; Received 18 August 2009; Accepted 29 October 2009; Published online 9 December 2009

Phylogenies reveal new interpretation of speciation and the Red Queen

Chris Venditti1, Andrew Meade1 & Mark Pagel1,2

School of Biological Sciences, University of Reading, Reading, Berkshire, RG6 6BX, UK

Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde Park Road, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501, USA

Correspondence to: Mark Pagel1,2 Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.P. (Email: m.pagel@reading.ac.uk).

Topof page

Abstract

The Red Queen1 describes a view of nature in which species continually evolve but do not become better adapted. It is one of the more distinctive metaphors of evolutionary biology, but no test of its claim that speciation occurs at a constant rate2 has ever been made against competing models that can predict virtually identical outcomes, nor has any mechanism been proposed that could cause the constant-rate phenomenon. Here we use 101 phylogenies of animal, plant and fungal taxa to test the constant-rate claim against four competing models. Phylogenetic branch lengths record the amount of time or evolutionary change between successive events of speciation. The models predict the distribution of these lengths by specifying how factors combine to bring about speciation, or by describing how rates of speciation vary throughout a tree. We find that the hypotheses that speciation follows the accumulation of many small events that act either multiplicatively or additively found support in 8% and none of the trees, respectively. A further 8% of trees hinted that the probability of speciation changes according to the amount of divergence from the ancestral species, and 6% suggested speciation rates vary among taxa. By comparison, 78% of the trees fit the simplest model in which new species emerge from single events, each rare but individually sufficient to cause speciation. This model predicts a constant rate of speciation, and provides a new interpretation of the Red Queen: the metaphor of species losing a race against a deteriorating environment is replaced by a view linking speciation to rare stochastic events that cause reproductive isolation. Attempts to understand species-radiations3 or why some groups have more or fewer species should look to the size of the catalogue of potential causes of speciation shared by a group of closely related organisms rather than to how those causes combine.

School of Biological Sciences, University of Reading, Reading, Berkshire, RG6 6BX, UK

Santa Fe Institute, 1399 Hyde Park Road, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501, USA

Correspondence to: Mark Pagel1,2 Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to M.P. (Email: m.pagel@reading.ac.uk).

+++++

Professores, pesquisadores e alunos de universidades públicas e privadas com acesso ao site CAPES/Periódicos podem ler gratuitamente este artigo da Nature e de mais 22.440 publicações científicas.

+++++

Os itálicos são deste blogger cético da onipotência, onisciência e onipresença de quaisquer mecanismos evolutivos, seja a seleção natural e toda a seleção de mecanismo evolutivos de A a Z explicarem a origem e a evolução da diversidade das coisas bióticas,

You might also like/Você pode gostar também de:

[/center]

- Darwin também errou sobre a seleção natural

- Teoria da evolução: nem de Darwin, nem de Wallace

- Horizontal e vertical: a evolução da evolução

- O que W. R. Thompson disse na introdução ao Origem das Espécies discorda dos vídeos do Yale Peabody Museum

Carlstadt- Administrador

- Mensagens : 1031

Idade : 48

Inscrição : 19/04/2008

Tópicos semelhantes

Tópicos semelhantes» A árvore da vida de Darwin cai por terra

» Árvore da Vida de Darwin é uma miragem ideológica!

» Árvore da Vida Darwin está cada vez mais podre

» Arvore da vida de Darwin é "errado e enganoso", afirmam cientistas

» Craig Venter nega existência de uma Árvore da Vida de Darwin ???

» Árvore da Vida de Darwin é uma miragem ideológica!

» Árvore da Vida Darwin está cada vez mais podre

» Arvore da vida de Darwin é "errado e enganoso", afirmam cientistas

» Craig Venter nega existência de uma Árvore da Vida de Darwin ???

Permissões neste sub-fórum

Não podes responder a tópicos

Início

Início

Seja fã Forumeiros

Seja fã Forumeiros

» Acordem adventistas...

» O que Vestir Para Ir à Igreja?

» Ir para o céu?

» Chat do Forum

» TV Novo Tempo...

» Lutas de MMA são usadas como estratégia por Igreja Evangélica para atrair mais fiéis

» Lew Wallace, autor do célebre livro «Ben-Hur», converteu-se quando o escrevia

» Ex-pastor evangélico é batizado no Pará

» Citações de Ellen White sobre a Vida em Outros Planetas Não Caídos em Pecado

» Viagem ao Sobrenatural - Roger Morneau

» As aparições de Jesus após sua morte não poderiam ter sido alucinações?